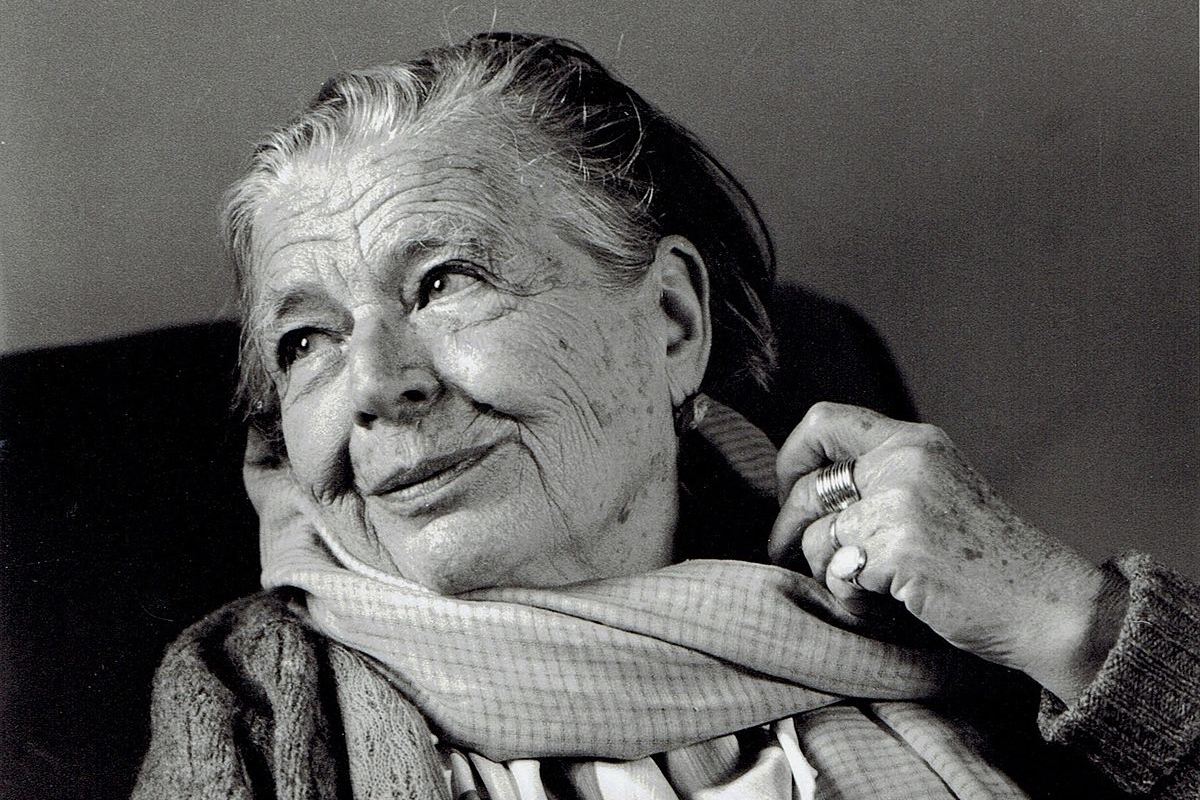

Marguerite Yourcenar, on a visit to Ravenna in 1935, wrote in “Ravenna or Mortal Sin”, a chapter that later became part of the posthumous collection “Pilgrim and Foreigner” (1989):

“One of the secrets of Ravenna is that stasis borders on supreme speed: it leads to vertigo. The second secret of Ravenna is the ascent to the deep, the enigma of the Nadir. Quite literally, the characters in the mosaics are mined: they have dug into themselves huge caverns, where they gather God. Submerged within the viscera of ecstasy, they set off in search of a midnight sun, toward the mystical antipode of day. Their experience contradicts the Gothic impulse of arms outstretched towards God. Locked in a dream, imprisoned under the diver’s bell of the domes, they escape the frenzy of the world in the serenity of the abyss.”.

(M. Yourcenar, En pèlerin et en étranger, Éditions Gallimard)

Therefore, an unavoidable contradiction remains for Yourcenar, inextricably bound up in the splendour of the past, the gold of the imperial era, the basilicas radiant with light, the ultramarine blue and emerald green of the ancient mosaics, and the slow inexorable decline that followed in successive centuries of ecclesiastical domination. The stagnant watercourses, swamps and marshes that surrounded the city like the walls and strongholds that encircled its outer perimeter reflect that immobility.

“There is no other city where the gap between inside and outside, between public life and the secrecy of solitude, is felt more acutely. In the square the sun warms the iron chairs in front of the door of a café. Dirty children, women bursting with maternity wander the streets sadly. But here in this purity of darkness, soon made transparent by habit, clear fires gleam here and there, like those of a soul in which the crystals of misfortune are gradually formed.”