Sweet hour of twilight! – In the solitude

Of the Pine forest, and the silent shore

Which bounds Ravenna’s immemorial wood,

Rooted where once the Adrian wave flowed o’er,

To where the last Cæsarean fortress stood,

Evergreen forest! which Boccaccio’s lore

And Dryden’s lay made haunted ground to me,

How have I loved the twilight hour and thee.

(Don Juan Canto 105, 1821)

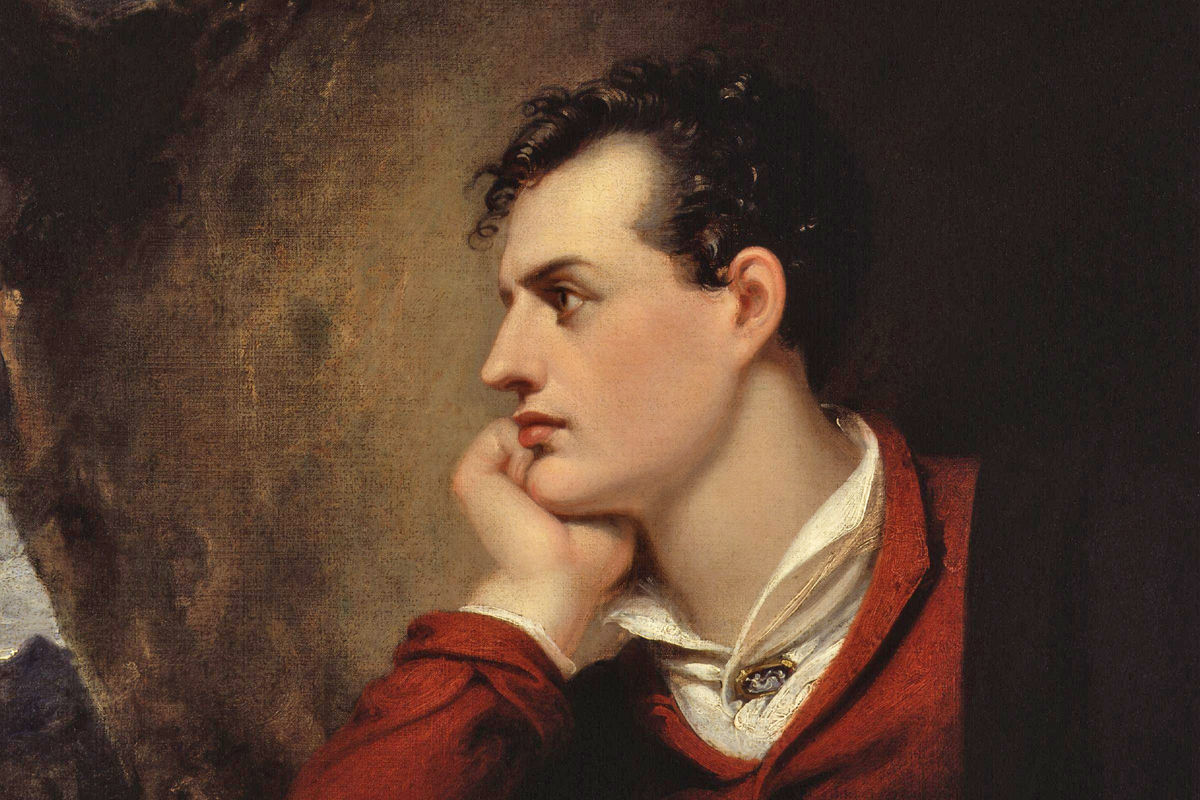

Insatiably in pursuit of emotional excitement, the fame of LORD GEORGE GORDON BYRON, one of the greatest British poets, is due above all to his romantic and excessive lifestyle, political and literary scandals, heroic and revolutionary adventures and brazen womanizing, a number of which were notched up in Italy. After deciding to leave England never to return, he sojourned first in Milan from 1816, then in Venice and finally from 1819 in Ravenna, following his beloved Teresa Guiccioli.

The pine forest along the Ravenna coast in Classe, mentioned in the satirical epic poem published posthumously, Don Juan (in Italian Don Giovanni), was for Byron an ideal environment, because it was wild and attractive, highly symbolic as a source of artistic and literary inspiration and a natural mirror of the romantic temperament of Sturm und Drang.

His publisher, Thomas Medwin, reports how during his stay in Ravenna (1818-1821), Byron was never tired of exploring the pine forest, on foot or on horseback. Here, as the poet himself writes in the third canto of Don Juan, he breathed in the fables of Dryden, the togetherness of the people in Boccaccio’s Decameron and the majesty of prophecy in Dante’s Comedy: “There is something stimulating in this air”, he confesses (Conversations, ed. Lovell, p.25).

Piero Gamba, brother of his beloved countess Teresa Guiccioli, for whom he had come to Ravenna as a guest at his brother-in-law’s palace in Via Cavour, tells how, at the end of a ride in the forest, Byron declaimed:

How, raising our eyes to heaven, or directing them to the earth, can we doubt of the existence of God? – or how, turning them to what is within us, can we doubt that there is something more noble and durable than the clay of which we are formed?