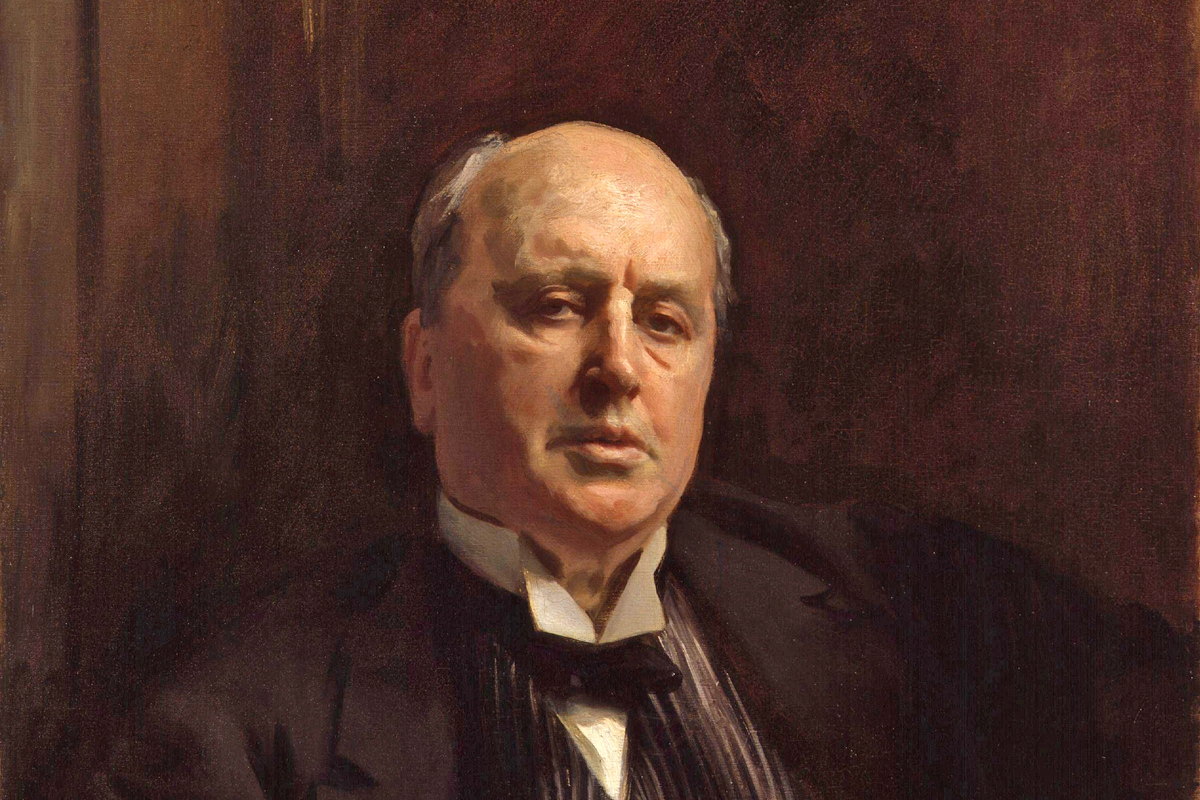

“For Ravenna, however, I had nothing but smiles – grave,

reflective, philosophic smiles, I hasten to add,

such as accord with the historic dignity (…) of the place.

I spent the rest of the morning in charmed transition between the hot yellow streets and the cool grey interiors of the churches. The greyness everywhere was lighted up by the scintillation, on vault and entablature, of mosaics more or less archaic, but always brilliant and elaborate, and everywhere too by the same deep amaze of the fact that, while centuries had worn themselves

away and empires risen and fallen, these little cubes of coloured glass had stuck in their allotted places and kept their freshness”

(Henry James, Italian Hours)

It would be possible to theorize that James’s novels are not so much about characters as about epochs, cultures and social spheres. It is the encounter, often in the form of a clash between cultures and affiliations (one American, the other English), that offers the ideal terrain on which James builds part of the characters’ psychology and a narrative, in which the subjective point of view and the technique of the inner monologue abound, marking a turning point in the modern novel. In this sense, the journey Henry James made to Italy and his stay in Ravenna, a city to which 11 pages of his collection Italian Hours (Ore italiane) written between 1872 and 1909 are dedicated, were invaluable.

Pages that, even today, are fascinating and extremely precious; interwoven with visions, or rather descriptions of environments and atmospheres that take us back to a Ravenna full of excitement, lavish and artistically exhibited treasures exuding remarkable power, if only because of the resonances of the past that resurface everywhere.

In fact, James writes:

“It is as if history had burrowed under ground to escape from research and you had fairly run it to earth.(…)

wherever you turn you encounter some fond appeal to your historic presence of mind.”

And of the chapel of Galla Placidia:

“This is perhaps on the whole the spot in Ravenna where the impression is of most sovereign authority and most thrilling force.”

Spontaneous and engaging, James guides us with great empathy through the streets and squares of Ravenna, as he does when he simply writes:

“For Ravenna was glowing, less than a week since, as I

edged along the narrow strip of shadow binding one side of the

empty, white streets”.

And then dedicates his attention, as did his even more illustrious predecessors, to the intersection between art and nature, between history and the present, between reason and sentiment, when he arrives in Classe and the majestic spectacle of Sant’Apollinare opens before him:

“(…) Between the city and the forest, in the midst of malarious rice-swamps, stands the finest of the Ravennese churches, the stately temple of San Apollinare in Classe. The Emperor Augustus constructed hereabouts a harbour for fleets, which the ages have choked up, and which survives only in the title of this ancient church. Its extreme loneliness makes it doubly impressive. They opened the great doors for me, and let a shaft of heated air go wander up the beautiful nave between the twenty-four lustrous, pearly columns of cipollino marble, and mount the wide staircase of the choir and spend itself beneath the mosaics of the vault. I passed a memorable half-hour sitting in this wave of tempered light, looking down the cool grey avenue of the nave, out of the open door, at the vivid green swamps, and listening to the melancholy stillness”.