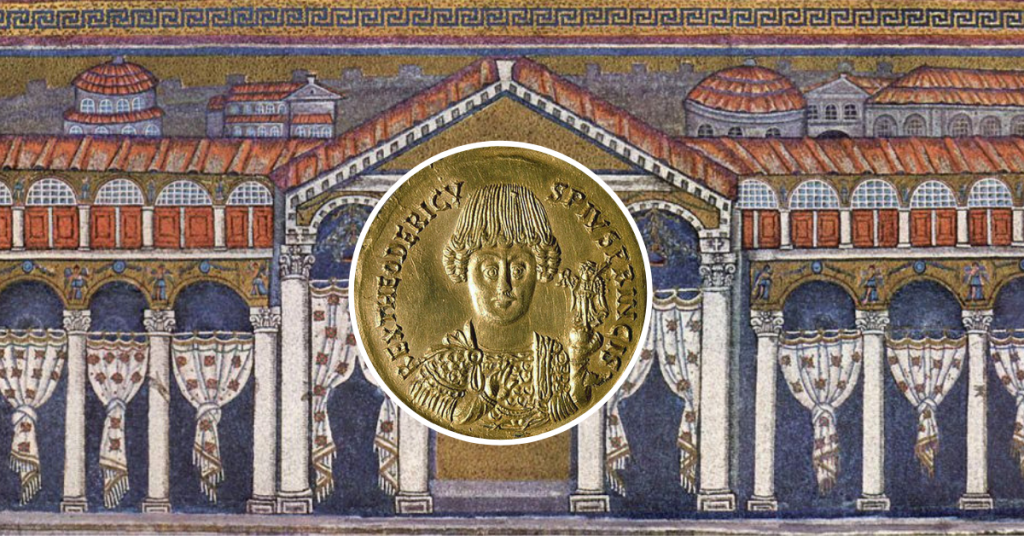

Among the monuments in Ravenna that have been declared part of the UNESCO World Heritage Site, the Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo stands out thanks to its fascinating mosaic decoration.

Built as a palatine chapel by the Ostrogothic King Theodoric after his conquest of Ravenna in 493 AD, the church was adorned with sumptuous mosaic decorations with the explicit intent to celebrate the new sovereign and his court.

After the return of the city into the hands of the Byzantine Emperor Justinian, in 561 an edict decreed the re-appropriation of Arian possessions to Orthodox Christians, with the following removal or modification of the parts of the figurations considered inappropriate or in stark contrast to the directives of the new government.

And so it was that the first mosaic panels in the central nave of the basilica were “censored”, especially those depicting the barbarian sovereign, and at the same time were enriched by the marvelous processions of the saints that even today keep us company from the building’s entrance to the area of the Basilica’s apse.

Dazzled by their beauty, rarely do we realize an unusual presence on the interior wall of the church’s façade: here – to the right of the entrance door – is a portrait of a male figure, usually covered in shadows and in a rather neglected position.

With a round face and white hair, he wears the same cloak closed by a fibula (a type of pin) and crown adorned with pendilia that we can admire on the head of Justinian in the apse panel in the Basilica of San Vitale. The head is nimbused and in the upper part is an inscription that identifies him as «Ivstinian».

And yet, comparing the physical characteristics of this portrait to the Imperial portrait in San Vitale, it is difficult to believe that it depicts the same person.

Studies have tried to explain these differences in various ways, starting from a re-examination of the ancient sources and restorations that have occurred since the time it was originally produced.

The early historian Andreas Agnellus in his Liber pontificalis from the 9th century had already cited the presence of the portrayals of Justinian and Archbishop Agnellus inside the church.

In the following centuries, these presences were confirmed, flanked by a third figure placed lower than the others. The identifications vary: some don’t believe it to be Angellus but Theodora and all inform us about the terrible state of conservation of the mosaic.

Object of restorations and important integrations by the hand of Felice Kibel in 1863, when the identification with Justinian was still well-established, since 1927 the portrayal was subjected to attentive studies that ascertained the creation of the figure in different eras. The face and neck date back to the age of Theodoric, whereas the Imperial attributes have been added at a later time, during Agnellus’ purging of Arian and Ostrogothic influences.

Based on these interpretations the face is not that of the Emperor, but of Theodoric, later “disguised”as Justinian.

The practice wasn’t so unusual at the time, given the sacred significance with which the Byzantine basileus was invested. More divine than human, his royal likenesses passed to secondary importance with respect to the regal symbols attributed to his status and power.

In the second half of the 19th century however, several doubts and concerns were put forward regarding the identification of the figure with Theodoric.

A more attentive examination of the existing portrayals of Justinian identified the existence of a “realistic” current, an example of which is the golden medallion in the British Museum of London, where the sovereign appears with swollen cheeks and heavy eyelids, traits comparable to the image present in Sant’Apollinare Nuovo.

In light of these studies, in 1999 Isabella Baldini Lippolis proposed identifying the mosaic fragment as a survivor of a more substantial decoration from the Justinian era, in which the Emperor and Bishop Agnellus appeared on the sides of the entrance to the building, perhaps accompanied by the image of a defeated barbarian.

Their presence at the Church threshold would have had the purpose of introducing the newly re-consecrated place to the true Orthodox faith and to reaffirm the full identity between the city’s clergy and Imperial power.